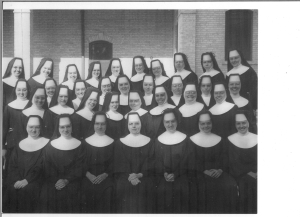

Most of my moving experiences in California were predictable. With no money after leaving the convent and finishing my Master’s at the University of St. Louis, I stayed with my youngest sister and her family in the East San Fernando Valley to get my bearings and my first teaching pay checks. I then moved my meager belongings to inexpensive apartments near her, also in the East Valley. After meeting my husband in 1968 and our marriage early the next year, we lived in apartments in Los Feliz and Hollywood until we knew we were to have a child. Our first house in the West Valley cost $18,000 and our first car about $1800. But we needed more room when we were surprised by the arrival of twins. The house we purchased in North Hollywood stretched our budget since I had stopped working, but it had a nice yard, good neighbors and the potential for add-ons, which we made in 1980.

We lived in that house for 22 years before hearing the call of duty. Steve’s sister, living in Wilmington, North Carolina was dying of cancer with two children aged 9 and 13. Their father Jock’s work in the movie business often took him far from home and their grandmother, Kay Taylor, could not care for them adequately at her age. We decided to leave Los Angeles and our teaching and legal work to assist Jock with the children. I was quickly hired to teach at the local community college for a semester and then moved to the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. Steve became a member of the North Carolina Bar and ended up securing an appointment as a magistrate instead of practicing law. Kay helped us pay for a large home in Wilmington’s downtown historic district with two spacious bedrooms for Darwin and Maaike. But Fate stepped in once again, as Jock decided to limit his film work to what could be done locally and keep the children with him, just asking our assistance as needed. The Dock Street house became the extended family party and celebration site as well as a center for book club and political meetings. We lived there for fourteen years during which time our son moved to Wilmington (in 2005) and our daughter lived in nearby Chapel Hill to finish her Surgical ENT residency at UNC.

It was the next move – to Philadelphia and to Walnut Creek, California – that was unique. If I wanted to be dramatic, I could say it was a story of suspense, betrayal, greed and the kindness of strangers.

Since we were moving some of our furniture across country, we thought we would play it smart and put our necessary belongings in a “pod,” a large container that would be trucked to a depot in California near where we hoped to settle. How simple, how convenient: just throw the essentials into a pod placed next to our house, take what other things we could in a small trailer up to our half-year home in Philadelphia and give away or sell the rest.

Enter the Municipal Bureaucrat: “Sorry, sir, you cannot leave that pod by your house there, against our rules, slows down traffic, irritates the neighbors, and worst of all, doesn’t give me a chance to flaunt my authority.” Cough up an additional $400 to hire Two Men and a Truck to twice load their smaller truck, haul it down to the local pod depot, reload there. But wait, first there’s the sale – we need to shrink the contents of a 3000 square foot home to make them fit into a 900 square foot California condo. Piece, albeit a fairly large piece, of cake.

Through a series of missed communications and family-related brouhahas, we find we have only six days to rid ourselves of what seemed like 1000 items. We advertise our sale and of the forty or so items we put on Craigslist, we find we are able to sell exactly one of them – a seventies-style Scandinavian chair which seven people inexplicably coveted – for $20. Advice learned too late: keep reposting items on Craigslist every day since each sinks to the bottom of its respective list. But, by happenstance, we were able to sell items not posted.

A friend from my book club came to help us pack and brought her daughter who made a clever for sale signs to hang over our realtor’s For Sale sign. We rented tables and made tiny price stickers for all the goods accumulated (not only during our last 16 years but also those bequeathed to us by others). We quickly find out that our sale hours, Sunday, 2-6, are not buying hours for our potential customers (those buying hours would be early on a Saturday, but we weren’t home Saturday: a shirt-tale family wedding had taken priority over the things which are Caesar’s).

Yet various friends, neighbors and panhandlers do wander through. And by chance they needed– cheap – a nearly new set of suitcases, an antique desk, a unique 1920’s full length mirror, our pots and pans, a Queen Anne chair, a rose marble-topped coffee table, our beds and dressers and a few pieces of original art. Also, maybe not by chance, they did not need 29 lovely picture frames; jewelry unless it was free; cd’s; dvd’s; hundreds of classic vinyl recordings, and a multitude of household items unless they were free. We offered free books to all who entered – we had given thousands to libraries and the university but had retained some 300. One dear stranger almost wept when I offered him, free of charge, a leather-bound illustrated Complete Works of Shakespeare for his poetry-loving daughter. After receiving an original Harry Davis painting for a favor he did us, one young black teenager delightedly offered $2 for a work by another local artist, Ivy Hayes.

At that point, we realized giving away was more fun than selling, so we started an outdoor street corner sort of “sale.” We put outside near the street a sewing machine, an espresso machine, a juicer and a food processor, all relatively unused with a large sign reading “Guaranteed – all appliances work, or your money back.” Of course, one guy knocked on our door to ask if the juicer worked. In any case, each appliance disappeared in about 20 minutes. When we put out a relatively unused (naturally) ironing board, the cover of it disappeared, but the skeleton remained, leaning against the fire hydrant. For some reason no one wanted the silk tree. Room on the corner and immediately in front of the house being limited, we kept replacing our giveaways. Almost all our Christmas decorations, games, random bowls and other dishes, and knick-knacks disappeared. Steve’s mother had left a modern style tall transparent blue vase which glass stores did not want. Several young visitors liked it and started a bidding war for it. After the rivals for it left, the winner had to go to the bank to get the $40 to pay for it. He never returned, and the vase now sits near our daughter’s fireplace, just as her grandmother had placed it near hers.

As we wondered how to get rid of our cupboards of food quickly, in walks a 6′ 11″ handsome stranger who looked around, offered to help and told us of a book on Tennessee Williams he had written and expected to make a killing on. But in the meantime he subsisted on food from Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard, a local soup kitchens. Serendipity in action: he brought several boxes from his newly acquired (somehow) digs nearby and loaded every can, box and bottle from our pantry cupboards and freezer, making several trips back and forth, constantly regaling us with stories of a past of betrayal and a future of extreme wealth.

Now our remaining earthly goods were down to a reasonable load. We called Goodwill to pick them up. They needed 10 days notice. We called Salvation Army, which needed seven. Next we tried Habitat for Humanity. They were closed for remodeling, as was another charity. Our deadline for being out of the house nearing, we had only our dumpster for sympathy and recourse. Then a bed, some cleaners and a dinner for the new owner moved in. Panic. Throw faster. Wrap and box more efficiently. Luckily the new owner came and said we should leave usable stuff. We thus left a year’s supply of Costco-acquired paper goods in the back storage room as well as the ten-pound bottle of dishwasher liquid. We also left a giant green plastic tub which had on top several black winter boots and who-knows-what underneath, probably woolies we once fantasized would be worn for Lake Tahoe skiing.

Completely brain dead after all this, we climbed in our Buick, lashed up the trailer and pointed it north.